I had the fortune of joining a many-to-one video conference with Ed Snowden in August in Berlin.

Perhaps counterintuitively, it left me feeling rather optimistic about our current direction in regards to privacy both online and in our society, a feeling that contrasted sharply with the gloom I felt after first seeing Citizen Four by Berlin-based filmmaker Laura Poitras. My optimism was informed by a variety of thoughts, namely that:

(i) Ed Snowden is a controversial figure, and rightfully so. Yet here is an individual who sacrificed a tremendous amount in his own life to help bring systemic violations to human liberty into public awareness. However we feel about his first acts, the facts he brought to light have helped us confront challenges to privacy with greater transparency. That he himself was originally culpable and a part of this system clearly brought a level of urgency and raised the stakes regarding the set of choices he had to make.

(ii) For most of us the relevant choices are trivial in comparison. They boil down largely to choosing privacy over convenience, participating in our societies in a fashion consistent with the idea that privacy is a human right, and holding the products and services we engage with online accountable to that same ideal.

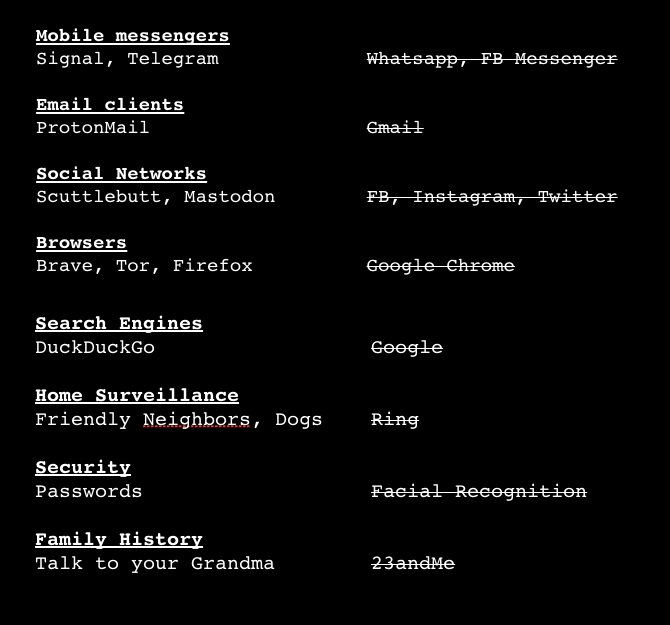

Luckily, the gap between true privacy and high quality user experiences in consumer software is narrowing. Before, you may have had to mess around with your own PGP keys to send and receive encrypted emails. Today, for example, you can use ProtonMail. Before, WhatsApp, Facebok Messenger and WeChat were clearly the leaders in terms of mobile messenger UX. Today, Telegram and Signal provide far greater privacy (not to be confused with end-to-end encryption, Facebook still plans on opening WhatsApp up to “businesses in your community”), with quasi feature parity. Organizers of protests in Hong Kong can now effectively communicate on Telegram without sacrificing convenience. What these privacy-focused solutions often don’t have are as-robust social graphs, meaning not everyone you care about will be on them, but that’s for us to change.

Speaking of social graphs, there are various worthwhile efforts at recreating social networks. Some are based on topics (like gaming) and take a pseudonymous approach, like Discord. Others are trying to create a truly p2p version of a social network, notably Scuttlebutt which feature-wise is attempting to replace a lot of what FB did in the early days, or Mastodon, which is a more p2p version of Twitter. If you want privacy from your browser, you can look to Brave or Tor, and if you want privacy while you search you can use DuckDuckGo, who has built a profitable advertising business without resorting to “we know you better than you know yourself” targeting. Even if you want to stay with your current ecosystem of apps, but better manage configs and permissions, apps like Jumbo Privacy can help you do that.

So the trade-offs we have to make in favor of privacy are getting easier, even as awareness of the cost of the status quo (which supports surveillance, direct personal data monetization, and personal data vulnerability through poor security and storage) expands.

iii. Since Snowden brought institutionalized online surveillance programs like PRISM and XKeyScore to our attention in 2013, privacy has become a daily front-page issue for publications and boardrooms around the world. Alongside this narrative has been the slow realisation that most companies simply cannot be trusted with our own personal data (go have a look at Have I Been Pwned and see for yourself). Luckily, in the relatively short six years since, the European Union has put into law the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, implemented in May 2018), which states that “The protection of natural persons in relation to the processing of personal data is a fundamental right”. GDPR outlines a comprehensive framework that fundamentally changes how businesses and services must collect, process and treat personal data. Enforcement has so far been muted in my view, while authorities allow for some adjustment time, but I believe major enforcement is a question of when, not if.

Europe is not alone in terms of front-footed policy making on privacy. California passed the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA, enforceable beginning January 1, 2020) last year. The Act begins with a reminder that a fundamental right to privacy for all is recognized and protected by California’s constitution. These policies have been a critical impetus in ensuring that citizens and market participants treat counterparty data with more respect. The bills have also created huge opportunities for companies focused on privacy software that help businesses bridge the wide gap between what policymakers are signing into law and the privacy-jeopardizing status-quo of the past few decades. Companies that are seizing this opportunity include Collibra, Onetrust and DataGuard

iv. I used to hear the oft-repeated defence of “Why should I care about privacy if I have nothing to hide?”. Slowly, that sort of naive collective thinking is starting to fade away. My partner remarked to me that you hear that refrain most often from citizens of countries like the UK and US, who have by and large not had a reason to fear their governments in the past few decades. You won’t hear that from Berlin residents who are old enough to remember the Stasi or older residents of Eastern Bloc countries. You won’t hear it from protestors in Hong Kong, or families in South Texas huddling in fear of ICE raids. Slowly we are all realizing that it is not just terrorists and criminals who have something to fear from unfettered surveillance. Slowly we are all realizing that the proper time to make decisions to safeguard our civil liberties is when doing so may seem foolish, because when it doesn’t it may be too late.

Luckily, the steps we have to take today don't seem as foolish and aren't as hard as they were yesterday.